To Sing for the Whole World

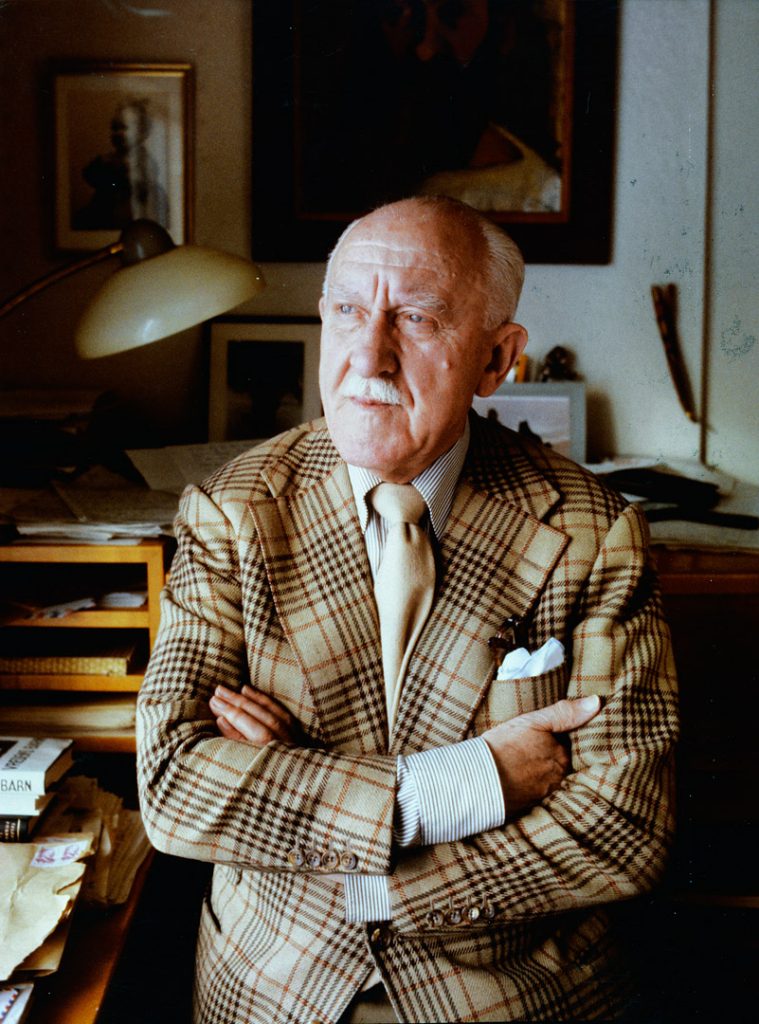

‘It’s good to have him back’, said the Washington Post when Halldór Laxness’ Independent People was reissued in the USA last year. But for his devoted readers in Iceland and other European countries he has always been there.

Halldór Laxness’ career extended over an unbelievable length of time. His first novel was published a year after the end of the First World War and his last book, Days among Monks, in which he writes about his sojourn in a monastery in the 1920s, came onto the market two years before the fall of the Berlin Wall. During all this time – nearly 70 years – he remained prominent both in the national life of Iceland and in the European cultural scene. He produced 62 works of literature in 68 years, almost a book a year.

The Century of Halldór Laxness

Laxness’ works have always attracted attention and from the first the Icelandic nation was split into two camps according to whether they were for or against him. No one could be indifferent to his books. In addition, he was an indefatigable essayist, writing newspaper articles about everything under the sun. He was not slow to embrace the impassioned class politics of the 1930s; wrote countless articles about cultural issues; took up the cause of horses left out to graze all year round, as he felt the way they were treated was a national disgrace at the time; extended his interests to environmental issues, to every aspect of national affairs, and so one could go on. No human issue was beneath his notice – he had views on everything. And whether people agreed with him or not, his writings were invariably taken seriously – they were always important. It is rare to find a writer who has involved himself so wholeheartedly in his nation’s destiny, interpreting it through his works and at the same time trying to have an influence on its progress. Halldór Laxness was born when this century was two years old and took his leave with only two years of it left to run. He had lived through the greatest century of change in the course of Icelandic history and participated in bringing an entire nation out of the Middle Ages into the modern world. It is no wonder then that it was said on his death on 8 February 1998 that the 20th Century in Iceland had been the century of Halldór Laxness. He had long been considered a controversial figure due to his political views, but after he received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955, the whole nation can be said to have united behind him.

A Unique Career

Halldór Laxness stands head and shoulders above the other Icelandic writers of the 20th Century. He was prolific during his long career, writing thirteen major novels, five plays and a dramatisation of one of his novels, not to mention his collections of short stories, essays and memoirs. His books have been translated into 43 languages and have been published in more than 500 editions. They have sold in large numbers all over the world, e.g. hundreds of thousands of copies in the USA alone. His career is unique, the diversity of his works almost without parallel, and with every book he can be said to have approached his readers from a new and unexpected direction.

In recent years there has been a reawakening of interest in the publication of his works, not least in Germany where Steidl Verlag has published his main works in a new series, in which Professor Hubert Seelow has retranslated the books or revised older translations. While the English-speaking world, which has been deprived of his works for decades, has finally roused itself.

I must do or die!

Laxness knew early what his purpose was in life. He wanted to be among the top-ranking writers in the world – ‘he was to sing for the whole world’, as is said of the son of Bjartur of Summerhouses in Independent People. He wrote constantly in his youth, his first novel seeing the light of day in 1919. He then travelled abroad and stayed in Copenhagen where among other things he had a short story published in Danish on the front page of the weekend edition of Berlingske Tidende, the most important newspaper in the country. A few days before the story appeared, on 10 October 1919, he wrote in a letter to his mother;

‘I feel so clearly that this journey [to Copenhagen] is a great step towards what I am searching for, that is to say, towards a knowledge of people and the world, so that I can become a real writer, which preoccupies all my thoughts’.

For a while he considered writing in Danish as various of his fellow countrymen had done so successfully, and wrote in a letter to his mother at Christmas, 1919:

‘I have promised myself not to come home until I have “made it” in Danish’.

Laxness decided, however, to keep to his mother tongue, and one can assert that no one else has played a greater part in renewing the Icelandic language during this century.

The 1920s were an important formative period in Laxness’ life. He spent some time in a monastery, wrote a novel in Sicily, and tried his hand at writing film scripts in Hollywood, before finally returning home, determined to become a successful novelist. During April and May of 1931 he sent his then wife, Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir, a letter from Leipzig in which he describes his struggles with a new book which is to be the second volume of a larger work;

‘I’m making excellent progress with the new book. I have great hopes of it – sometimes. – As you know – then in between times I am filled with despair. …[The subject matter] in many parts is tremendously difficult and intractable, and I spend day in day out in continual suspense as to what direction the story will take, the characters are developing more colossal dimensions by the day…. And if the second volume is successful, I’ll be “made”, I will have written a novel in a world format. … [There] are quite immense tasks ahead of me. And I must become a great writer on an international scale or die! There is no “pardon” and no question of giving in by so much as a hair’s breadth. I must do – or die!’

The novel in question is Salka Valka which tells a tale of ordinary people in a small fishing village. The first part came out in 1931 and at this time he was working on the second volume. It is clear from these fragments that the writer has a lot on his mind. He faces the future filled with zeal, the next great task already starting to impinge on his thoughts. Laxness obviously knows what he is capable of, but he has still not managed to make a breakthrough abroad by having one of his books published there. Yet his predictions were to come true. Salka Valka was his breakthrough in the foreign market and the book has now been published in 87 editions in 26 languages.

Like falling off Godafoss

Halldór Laxness’ literary works show great diversity, partly as a result of being written over a long period of time. In the 1920s he wrote a modernist novel with a surrealist vein, The Great Weaver from Kashmir (1927), as well as progressive poetry, while in the 1930s he wrote socio-realist novels, including Independent People (1934-35) about the farmer Bjartur of Summerhouses, ‘the story of a man who sowed his enemy’s field all his life, day and night. Such is the story of the most independent man in the country’, as it says in the book. In the 1940s he started to write historical novels, including The Bell of Iceland, his contribution to the Icelanders’ fight for independence, which was published 1943-46. Laxness wrote absurdist plays in the 1960s and, 40 years after he had written The Great Weaver from Kashmir, at nearly 70 years old, he began to flirt anew with modernism in novel-writing, along with a new generation of Icelandic novelists, in Under the Glacier. This book tells of an emissary of the bishop of Iceland who is sent to investigate the observance of pastoral duties by a priest who lives in the shadow of the Snæfellsjökull glacier. The priest has given up preaching the Christian faith, saying ‘Whoever does not live in poetry cannot survive here on earth’. When Laxness produced Under the Glacier in 1968, eight years had passed since the publication of his previous novel, Paradise Reclaimed, the tale of a farmer who abandoned his family and farm in order to travel halfway across the world in search of the Promised Land, only to return home later and find what he had been looking for in his own backyard. The writing of Under the Glacier seems to have put a great strain on Laxness and from his letters to his wife, Audur, which have not been quoted in print before, it can be inferred that he himself was doubtful about the outcome. On 5 October 1968 he writes to her from Copenhagen:

‘I’ve somehow still not pulled myself together following Under the Glacier;

it was a bit like falling off Godafoss [a waterfall]’.

And on 18 October Laxness writes to his wife of the book: ‘it was nearly the death of me’. Three days later he writes to Audur again, and has now obviously heard about the enthusiastic reception of the book in Iceland. He feels ‘pleased that various good people should be able to swallow a book like Under the Glacier without choking on it too badly. But no one knows better than myself in how many ways the book is deficient; but there is no point talking about it any longer’. Laxness received the Icelandic critics’ literary prize for Under the Glacier. It is worth mentioning that when the book came out in paperback in Germany in 1997, Der Stern newspaper said of it; ‘A mysterious tale of bizarre characters which brings tears of laughter to the eyes’. It has now been translated into 10 languages and has been published in more than 20 editions, and Laxness’ daughter, Gudný Halldórsdóttir, has made a film of the story, so the author’s lack of confidence in the book would seem to have been unfounded.

Constant revision

Halldór Laxness did not hold to one single beliefs or ideals. He began his career as a Catholic, then turned to socialism, but later lost interest in all doctrines – except perhaps Taoism – and his funeral in February 1998 was held in the Catholic Church in Reykjavík with combined Catholic and Protestant funeral rites. So one could say that he had come full circle. He never attempted to disown earlier views which he might have subsequently repudiated, regarding them instead as in instructive part of his make-up. Laxness’ most famous change of heart occurred when he settled his account once and for all with regard to the Soviet Union and Stalin in his book A Poet’s Time in 1963. ‘It is instructive to see how Stalin grew with every year into an increasingly text-book example of the way in which power draws the moral force out of men until a man who has achieved a complete dictatorship over his surroundings has in the process become totally immoral,’ as he says in the above book (p. 295). The publication of this book attracted a great deal of attention, but with hindsight it is possible to see how his attitudes were changing throughout the 1950s. In The Happy Warriors (1952) Laxness wrote a new ‘Icelandic Saga’, the action taking place in the Viking Age. He satirised the ancient hero-concept of the Icelandic Sagas, but the message of the story was no less applicable to the contemporary situation, as a belief in power and violence has long been the favourite expedient of those heads of state whose greatest fear is of their own subjects. Those who wished to could read there a criticism of Hitler and Stalin – of the cult of leadership – but the book also contains the complete opposite to those societies ruled by strong leaders or dictators, this model society being located by the author among the Greenlandic eskimos. These native people know no better than that all are equal and live in peace and harmony, and they have no leaders.

Respect for the Common People

Laxness’ ideals and beliefs changed with time and evidence of this can be seen to a certain extent in his works. Yet from the earliest period to the latest it is possible to detect the same basic themes in his books. He looked at things differently from other people, his writings were often barbed, and yet he always managed to see the comic aspects of his characters and their actions. His sympathy is invariably with the underdog. In fact, one could say that in his works he always promotes ‘the hidden people’, as he calls them, by which he does not mean the hidden people or elves of Icelandic folklore which live in rocks, but rather the common people. It seems fair to say that respect for these people is at the heart of Laxness’ work. We see it in his epic novels, whether he is writing about the fisher-girl, Salka Valka, the farmer Bjartur of Summerhouses, or Icelandic heroes of the Saga Age. We also see it in the author’s essays, as he produced numerous articles on social issues. In the 1920s he was busy teaching the nation to wash itself and brush its teeth; in the 1940s he gave full rein to his thoughts on how a country which wants independence needs to behave if it is to gain respect and be taken seriously; in the 1970s he tried to bring the authorities to their senses over their treatment of the countryside in the spirit of latter-day conservationists, and so one could go on. He wanted his nation to have respect for themselves – for without this they could not hope to gain the respect of others.

The Hidden People and the Hype Society

Wherever Laxness travelled, he always took along a notebook in which he jotted down thoughts which occurred to him or things relevant to whatever he was working on at the time. In one such notebook from the 1960s, which is now in the care of Audur Laxness, Halldór’s widow, there appears a statement of his intention with regard to The Fish Can Sing, published in 1957, which could in fact be applied to the majority of works by Laxness. At the beginning of the notebook, which has not previously been quoted in print, the author makes a note of his intention in the novel:

“The Hidden People”, the ordinary “unspoilt” people – however infinitely frail from the standpoint of moral theology or other codes of ethics – the book is to be a hymn of praise to them, proof that it is precisely these people, the ordinary people, who foster all peaceful human values. The main character has his origin in the calm depths of the common people, and [the good people] he meets in his youth have the effect of making all the glory of the world seem worthless to him on the day when it is offered to him – as a result of the longing he feels to return home and experience once more the calm depths of ordinary human existence.

The Fish Can Sing, in other words, pays homage to the common people, who do their work out of devotion without boasting about it, a hymn of praise to ordinary human life and the people of whom Laxness was fonder than any others. And, as if to emphasise this, it says a little further on in the notebook;

Two kinds of Icelander: the fanatic extroverts, who are forever making a noise and showing off, making their mark on society and ruling the Hype Society – and then the Hidden People … who are endowed with almost everything men pride themselves on, but are wholly free from self-promotion, although they are the essential backbone, the element which is responsible for the fact that mankind has survived in Iceland, the people who perform all the great deeds but never boast of them, who one never hears about and who will never be discovered by the Hype Society.

In another place in the notebook he later defines ‘the Hype Society’ as follows;

‘The Hype Society – the collective responsibility of microscopic local celebrities to praise each other’.

The Hype Society is, in other words, what today is usually referred to as the Confederacy of Dunces.

Respect for All Lives

The Hidden People – the ordinary men and women – are thus the silent group which is custodian of all the values which have any worth at all. On reading The Fish Can Sing, one cannot avoid associating various values and views with it. The inhabitants of Brekkukot live an ordered, strictly traditional life, respecting other people’s right to be different and offering no man provocation. Words are too precious to waste in idle chatter, mischief or lies; curiosity and theft are regarded in the same light. The little croft on the edge of the small urban nucleus, which was beginning to develop in Reykjavik, seems very like Paradise. The people there have no faith in money or other such novelties. Grandfather and Grandmother at Brekkukot are the nicest of people and are rooted firmly in the past. To their way of thinking, the only true riches are those which cannot be taken away from one. These values have sometimes been described as Taoism, the core of Laxness’ Tao consisting of respect for all living things, a belief in simple human kindness, faithfulness and honesty. The model for human conduct, set down in a Chinese manuscript, The Book of the Way, more than two thousand years ago, is found by Laxness among the ordinary Icelandic men and women. These ordinary people – the Hidden People – are contrasted with the Hype Society; those who are forever pushing themselves forward without necessarily having any grounds for doing so.

Urgent Business with an Author

This respect Laxness showed for ordinary human lives explains in my opinion more than anything else why his works have enjoyed so much popularity among the Icelanders – and other nations as well. In his books one finds a common human core – a pure note – which appeals to people in the same way wherever they are, regardless of their environment. He succeeded through his works in bringing the greater world into Icelandic literature: in this microcosm the fates of his characters can be understood by people wherever they may live in the world.

Bjartur of Summerhouses, the main character in Independent People, would seem at any rate to have many doubles all over the world, and the book has made a deep impression on some readers. One winter, when Halldór Laxness was sitting at home in his house at Gljúfrasteinn, near Reykjavík, there was a knock at the door. Outside it was snowing hard and there was nobody about except those who had urgent business. There was a man standing at the door with a taxi waiting for him. He was an American on his way to Europe who had stopped over in Iceland to change planes. He had hailed a taxi and asked to be driven to Halldór Laxness’ house. It is about 75 kilometres from Keflavík Airport to Gljúfrasteinn and one can assume that such a journey cost a fortune. Yet the only thing he wanted was to shake the hand of the man who had created Bjartur of Summerhouses, get his autograph, and tell him that Bjartur of Summerhouses had more brothers in Manhattan than anywhere else in the world. He was in a hurry and did not have time for a cup of coffee, disappearing after a brief visit back out into the snowstorm. A man who drives 150 kilometres in a taxi on an errand like this must have been moved by the novel!

One of the Hundred Best

Independent People was the Book-of-the-Month Club’s main selection in 1946. Half a million copies sold in two weeks in the USA. Today Americans have welcomed the reissue of Independent People with open arms. Random House has had to reprint the book again and again (at the time of writing the 8th reprint is coming onto the market) and there seems to be no end to its popularity. Readers and critics alike have heaped praise on the book. Annie Dillard wrote in The New York Times; ‘In fact, it is one of the hundred or so best’. Dennis Drabelle said in the Washington Post; ‘There have been years – recent ones, in fact – when the Nobel Prize has gone to a little-known writer who emerged from obscurity only to fall quickly back into it. Halldor Laxness, happily, is a different case: a major writer from a small country whose work might have been lost to outsiders had it not been for the Nobel judges. It’s good to have him back.’

The voice of Halldór Laxness, who resolved in his youth ‘to sing for the whole world’, continues in this way to resound all over the world, even though he himself is now far away. And long may it continue to do so.

Grein í Iceland Review 1998